In 1978, Nancy Shedd was asked to speak at Juniata College’s annual May Day Breakfast. At the time, Nancy was directing the Historic Sites Survey for the Huntingdon County Historical Society. She and her crew of three CETA workers had been photographing and recording old structures all over the county for six months, and it was hard to think of anything else to talk about. But how was what she was doing relevant to the lives of the young college students she would be addressing? What follows is the answer she came up with — an answer that helps to explain the lure that research holds for those who engage in it and how it exercises the habits of mind that are formed by our education.

TAKING THE LIBERAL ARTS ON A FIELD TRIP

Nancy S. Shedd

Presented at Juniata College’s May Day Breakfast, 1978

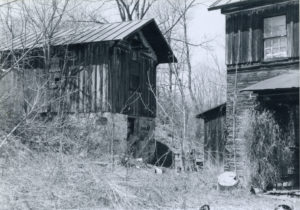

We turned the truck into the lane I had been told to watch for — a narrow, grassy track which took us down a gentle slope and then turned sharply right and dropped more steeply toward a weathered barn beyond the trees. Leaving the truck on the barn bridge, Gordon headed for the barn while I pulled my camera strap over my shoulder and started down the path through a double row of locust trees toward the house.

To my left, along the flank of the hill behind which the house still lay partially hidden, was a swath of daffodils in radiant bloom. The path I followed brought me through a tangle of rose and berry canes to a spot a dozen paces from the falling-down front porch of a small, weather-beaten brown house.

To my left, along the flank of the hill behind which the house still lay partially hidden, was a swath of daffodils in radiant bloom. The path I followed brought me through a tangle of rose and berry canes to a spot a dozen paces from the falling-down front porch of a small, weather-beaten brown house.

Saving the promise of the building’s two front doors for later, I took a path which led between the left side of the house and the open doorway of a two-story outbuilding built into the slope down which I had just come. The small stone room beyond the doorway contained only a broken barrel or two, and a familiar array of jars and old kitchen utensils.

Part of a roof of rusted tin and rotten boards lay across the path I followed where it passed between the back corner of the house and a heap of stone and brick which appeared to be the ruin of a sizable chimney. I speculated fleetingly on the size and placement of a former summer kitchen or washhouse which might explain this tumbled mass, then moved beyond the corner of the house and turned my attention to what the gaping cellar doorway might reveal.

Part of a roof of rusted tin and rotten boards lay across the path I followed where it passed between the back corner of the house and a heap of stone and brick which appeared to be the ruin of a sizable chimney. I speculated fleetingly on the size and placement of a former summer kitchen or washhouse which might explain this tumbled mass, then moved beyond the corner of the house and turned my attention to what the gaping cellar doorway might reveal.

The house was so placed on its site that although the porch and first story had been at ground level at the front, the full height of the foundation wall was exposed in the rear. As I moved still further down the slope toward what was actually a hole in the stone wall, from which the door and frame had disappeared, I saw a tiny stream of water running at the base of the hill. A glance into the cellar disclosed that the creeklet’s meagre flow was augmented at this point by water which oozed from the dirt floor of the basement, collected in a slime-covered pool just within the missing doorframe, then trickled through the deteriorating stonework to join the only slightly larger run beyond.

The cellar was empty. Hesitating a moment to consider whether the day’s light breeze was likely to bring the house down upon my head within the next few minutes, I ventured inside long enough to measure the first floor joists and summer beam and to record them in my pocket notebook.

The far side of the house revealed no reason to linger, so jumping the ditch worn by the basement stream, I returned to the front of the house and sought a vantage point from which to photograph the house’s brightly sunlit face. Gordon reappeared while I was thus engaged, and asked the obvious question, “Have you been inside?” “No, I was waiting for you.”

On the porch was a tangle of “things” so thoroughly mixed that I remember clearly only a wind-up alarm clock and the hose and brass wand from a garden sprayer. One of the doors was blocked completely, but the other looked approachable. Gordon turned the knob; the door did not seem to be locked, but did not open. He put his shoulder against it and pushed. It opened just far enough to reveal that the room within was filled to a level of two or three feet by a flood of “things” like those on the porch. Another shove pushed the door back far enough to allow us to launch ourselves onto the top of the unsteady mass, as Gordon issued fair warning to the house’s likeliest inhabitants: “Okay, rats, we’re coming in.”

On the porch was a tangle of “things” so thoroughly mixed that I remember clearly only a wind-up alarm clock and the hose and brass wand from a garden sprayer. One of the doors was blocked completely, but the other looked approachable. Gordon turned the knob; the door did not seem to be locked, but did not open. He put his shoulder against it and pushed. It opened just far enough to reveal that the room within was filled to a level of two or three feet by a flood of “things” like those on the porch. Another shove pushed the door back far enough to allow us to launch ourselves onto the top of the unsteady mass, as Gordon issued fair warning to the house’s likeliest inhabitants: “Okay, rats, we’re coming in.”

The confusion within was incredible: straight ahead, rising above the jumble of clothing, books, furniture, pans, and boxes on which we stood, was a cookstove with its own covering of pans, jars, and boxes. From sagging lines which crisscrossed the room hung articles of clothing as dingy and nondescript as the clothes or rags heaped on the floor. This was not a washing hung to dry, but overcoats and army shirts and shapeless, colorless trousers flung over, not pinned, to the line. Only one clothespin had been used. It gripped the quintessential battered man’s felt hat — the very Platonic ideal toward which every filthy, shapeless example you have ever seen is tending. Flat on its face in the middle of the room, balanced somewhat precariously atop the shifting mass, was a full-size corner cupboard, and in a heap just beyond it, a small rusting mountain of every size of pipe tobacco can known to man.

Our eyes, becoming accustomed to the dimmer light, struggled to make sense of the disorder, to get a bearing on the lives we tramped beneath our feet. Behind the stove a string of hot peppers hung to dry; overhead neat bunches of pennyroyal for herb tea. Atop the parlor’s knee-high mass, a brand-new Honda maintenance manual and a heap of high school yearbooks from the 1920’s and 30’s. On a nail in the parlor wall, a man’s double-breasted blue gabardine suit askew on its hanger and a 1966 calendar for March. On a nail in the doorframe — handy for quick repairs — a roll of black electrician’s tape. And in the front of a moldy-looking ledger, pulled from the top layer of trash, a mother’s careful record: “John Smith, born December 24, 1912, weight 8 lb., length 18 1/2 inches,” and following that entry, a faithful record of his increasing size through every month of his first year.

Upstairs, among the broken feather pillows and naked mattresses, a brilliant red and rich green woven coverlet and an expertly pieced quilt in a strikingly different variation on the log cabin pattern. One upstairs bedroom lay six inches deep in letters, postcards, and photographs — sixty years’ accumulation, beginning before the mother of the household was married. Postcards from her future husband, often with no message and signed only with his initials. Sometimes the message was in the picture on the front — a couple picnicking beside a stream and the single word “Remember” written on the picture above the familiar initials. Cards to little Johnny from his aunts and cousins. Cards from friends at the seashore with an X marking their room, and one which read simply (and predictably) “The weather is fine. Wish you were here.”

Among the letters was one very official-looking tiny envelope whose return address read: “War and Navy Departments, Official Business.” I thought of all the Second World War movies I had seen in which the postman was the unwilling bearer of letters which began “We regret to inform you…” But no, it was a V-mail letter from John, who was in Germany, to his Mother.

Perhaps half an hour passed before I reluctantly left the fragments of the story scattered about that room, taking with me a half dozen snapshots of the house in its brighter days which I had found among the family photos strewn about. The house had another floor still unexplored.

The attic was crowded with remnants of a still earlier generation: a spinning wheel and broken yarn winder, a rope bed suspended from the ceiling, a plank bottom rocker. Every inch of space was filled, but this was the normal disorder of an attic, not the wanton trashing of the past which reigned below. Here too were the hoarded coffee jars and whiskey bottles which were, in this household, religiously stored away against a future need. And here too the neat strings of herbs hung to dry.

Hours have passed. The measuring and photographing we came to do have taken perhaps half an hour of that time. The mystery of other lives — of other ways of life — have kept us here. And do not let us go even though we leave the place. Going home, we compare mental notes, trying out this theory and that to explain what we have found. Throughout the evening we return again and again to some scrap of information we have forgotten to mention. At the end of the evening, Gordon says, “Let’s go to bed. I want to go through the place again in my mind while I’m falling asleep.”

What is the point? Why keep you from your studies this morning to spin you this tale? Because this is what, I think, when I wasn’t looking, my education prepared me to do. To recognize, first of all, that this simple structure — no Parthenon or cathedral, to be sure — was nevertheless worthy of careful observation and accurate recording. I have not detailed for you the reasons why I went to see and observe it myself, but suffice it to say, it was because it is an unusual type of construction which our survey has revealed is worthy of our attention.

But in entering that house, we got, as is so often the case, more than we bargained for. It is the brochure-writers’ claim that a liberal arts education prepares you not for a job, but for life; not for making a living, but for living itself. But what does that mean? To me it means, at least in part, developing the capacity to experience, and to enjoy, and to mull over, and eventually to store away, encased in amber, as it were, the totality of that afternoon: the quality of its light, the warmth of its sun, the yellow of its daffodils, the resurrection of its lives — the poetry of that day.

Without Steve Barbash’s art history classes, without Dewey Hoitenga’s philosophy classes, without Bob Thornburg’s literature classes — all of them here in settings as unpropitious as those described to you in Nancy Davis’s introduction — I would lack, I am certain, the knowledge, and the imagination, and the habits of thought which expanded that very ordinary experience into something much more deeply meaningful.

Who needs the great poets to tell one that all is vanity, when five miles from Huntingdon you can see for yourselves the ruins of what one family stored up against posterity: the letters, the photos, the family heirlooms, even the record of the still-living son’s birth — all in ruins, unvalued, ignored. But in that humble house I heard the lines of Shelley’s Ozymandias again, and they added meaning to the decay of those simpler lives which might otherwise have been lacking.

Who else but a liberally educated romantic would see in the melancholy example of that collapsing house a metaphor for the transience of all earthly things, yet a renewal of the conviction that all those things were not stored up in vain? For in those brief hours when their path crossed with mine, they were taken up just once more with the desire to understand — a desire fostered and made possible, I believe, by the mysterious groundwork laid in the classrooms of Juniata.

Ozymandias may stand headless in the sand, but someone should stand and look — and carry home the memory of that shattered visage.

OZYMANDIAS

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert … Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

“My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Percy Bysshe Shelley