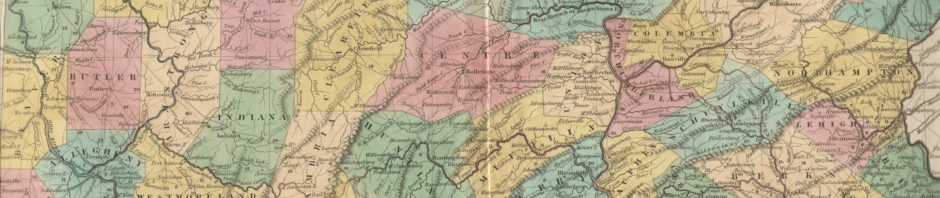

THADDEUS MASON HARRIS’S JOURNAL OF A TOUR INTO THE TERRITORY NORTHWEST OF THE ALLEGHANY MOUNTAINS, 1803

Harris, Thaddeus Mason. The journal of a tour into the territory northwest of the Alleghany Mountains; made in the spring of the year 1803: with a geographical and historical account of the state of Ohio; illustrated with original maps and views. Boston: Manning & Loring, 1805. [Library of Congress, American Memory, The First American West: The Ohio River Valley, 1750-1820. Also available at Google Books.]

Page 11 Thursday, April 7, 1803

Having ridden this morning from Shippensburgh, a distance of eleven miles, we stopped at Strasburg to breakfast.

As we approached the Alleghany Mountains, their form and magnificence became more and more distinct. We had, for several days past, seen their blue tops towering into the sky, alternately hidden and displayed by rolling and shifting clouds. Now, we ascertained that some of them were quite covered with trees; but that the rocky and bleak tops of others were naked, or scantily fringed with low savins [red cedar].

These stupendous mountains seemed to stretch before us an impassable barrier; but, at times, we could see the narrow winding,

Page 12

road by which we were to ascend, though it apprized us of the fatigue and difficulty to be encountered in the undertaking. Our apprehensions, however, were somewhat abated by information that, the way, though more steep, was not so rough, nor much more difficult than the Connewago Hills we had already passed.

Strasburg is a pleasant post-town in Franklin County, Pennsylvania. It is situated at the foot of the Blue Mountain, the first of the great range of the Alleghanies. It contains about eighty houses, principally built of hewn logs, with the interstices between them filled with flat stones and mortar. They stand on a main street, which runs from north to south. On the easterly side of the street, a little back of the houses, is a fine spring of excellent water, issuing from several fountains, over which are small buildings erected for the purpose of preserving milk, butter, and provisions, during the heats of summer. So copious is the issue of water, that it soon forms a considerable and never failing brook, which, within the distance of half a mile, carries a mill. This stream is the westerly branch of Conedogwinnet Creek, which

Page 13

falls into the Susquehannah opposite to Harrisburgh.

The inhabitants of this village are subject to severe rheumatic complaints, in consequence of the sudden changes of the weather in this vicinity to the mountain.

Near this place is shewn a large fissure in the side of the mountain, occasioned by the bursting of a water-spout. The excavation is deep. Trees, and even rocks, were dislodged in its course.

The first mountain, which is three miles over, was not so difficult to pass as we had apprehended. It is steep, but there are some convenient resting places; and the westerly side is rendered easy of descent by very judicious improvements in the condition and turnings of the road. The surface is very rocky; and the trees towards the top are small, and but thinly scattered. The stone which mostly prevails on its surface is granite, more or less perfect. At the foot is a beautiful and fertile valley, about half a mile wide, and fifteen miles long; irrigated by fine springs, whose streams uniting form the pretty brook that meanders through the fields and meadows of this enchanting place.

Page 14

We stopped here awhile, to let our horses rest, and to bask in the pleasant sunshine. Having been chilled with the air on the summit of the mountain, we were pleased with inhaling the warm breeze of the valley.

The contrast, between the verdant meads and the fertile arable ground of this secluded spot, and the rugged mountains and frowning precipices by which it is environed, gives the prospect we have contemplated a mixture of romantic wildness and cultivated beauty which is really delightful.

Hence we crossed the second mountain, four miles over, and stopped to dine at Fannetsburg, a little village on a graceful eminence swelling from the bosom of the vale. The houses are all built of wood, mostly of hewn logs, except our Inn, which is a handsome edifice of lime-stone.

In the afternoon we crossed the third ridge, which is three miles and an half over; in some places steep and difficult of ascent; and, passing part of the valley below, reached a place called Burnt Cabins to lodge. The settlement in this place is named from the destruction of the first buildings erected here, at the time of the defeat of Col.

Page 15

Washington, at the Little Meadows [sic – Big Meadows] in 1753.

The temporary buildings of the first settlers in the wilds are called Cabins. They are built of unhewn logs, the interstices between which are stopped with rails, calked with moss or straw, and daubed with mud. The roof is covered with a fort of thin staves split out of oak or ash, about four feet long and five inches wide, fastened on by heavy poles being laid upon them. “If the logs be hewed; if the interstices be stopped with stone, and neatly plastered; and the roof composed of shingles nicely laid on, it is called a log-house.” A log-house has glass windows and a chimney; a cabin has commonly no window at all, and only a hole at the top for the smoke to escape. After saw-mills are erected, and boards can be procured, the settlers provide themselves more decent houses, with neat floors and ceiling.

Friday, April 8 [1803]

A ride of thirteen miles this morning brought us to the foot of another mountain, called Sideling Hills, eight miles over. This is not like the others, a distinct ridge, but a succession of ridges, with long

Page 16

ascent and descent on the main sides, and intermediate risings and short vallies between.

It was a fine clear morning when we began to ascend. As we advanced, the prospect widened and became very interesting. The deep and gloomy valley below was a vast wilderness, skirted by mountains of every hue and form; some craggy and bare, and others wooded to the top: but even this extensive wild pleased me, and gave scope to boundless reflection.

Quitting the elevated region to which we had reached, we descended about half a mile, and then rose another and more lofty gradation. Hence the view was still more diversified and magnificent, crowded with mountains upon mountains in every direction; between and beyond which were seen the blue tops of others more distant, mellowed down to the softest shades, till all was lost in unison with the clouds.

As we descended, we beheld the mists rising from the deep vallies, and the clouds thickening around. It was cold and blustering, and we expected an immediate tempest and rain: but, as we mounted the third ridge, the clouds broke away over

Page 17

our heads; and, as they dispersed, the fun would shine between and give a gliding radiance to the opening scene. We soon got beyond the clouded region, and saw the misty volumes floating down to the vallies and encircling the lower hills; so that, before we reached the summit, we had the pleasure of looking abroad in an unclouded sky.

“Here could we survey

The gathered tempests rolling far beneath,

And stand above the storm.”

The whole horizon was fringed with piles of distant mountains. The intermediate vallies were filled with clouds, or obscured with thick mists and shade: but the lofty summits, gilded with the blaze of day, lighted up under an azure heaven, gave a surprizing grandeur and brilliancy to the whole scene.

The descent is in many places precipitous and rocky. At the bottom we crossed the Juniata in a ferry-boat. Climbing the steep banks of the river, our rout was along a range of hills exhibiting a succession of interesting landscape. In many parts we were immersed in woods; then again we came upon open ground, and saw the wind-

Page 18

ing river just below us, and the sides and tops of the mountains soaring above. Sometimes we rode, for a considerable distance, on the banks of the river; then we quitted it to mount a hill, and here again,

“The bordering lawn, the gaily flowered vale,

The river’s crystal, and the meadow’s green,

Grateful diversity, allure the eye.”

Such transitions yield some of the sweetest recreations which the varied prospect of nature can afford.

An accident in breaking our carriage, delayed us so long, that it was evening before we arrived at our Inn. We rode thirty miles this day.

Saturday, April 9 [1803]

While our carriage is repairing we rest at Capt. Graham’s, who resides in a delightful valley, belonging to Providence township, in Bristol [sic – Bedford] County. His neat and commodious dwelling is principally built with lime-stone, laid in mortar. The rooms and chambers are snug, and handsomely furnished; and the accommodations and entertainment be provides are the best to be met with between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Page 19

A fine lawn spreads before the house, bordered on one part by a meandering brook, and on the other by the Juniata river, from the margin of which rise the steep sides of Mount Dallas. The trees of other times add hoary greatness to its brow, and the clouds which rest in misty shades upon its head give it a frowning and gloomy pre-eminence.

The Juniata rises from two principal springs on the Alleghany mountains; one of which is very near the top, and pours a copious stream. It receives, also, supplies from many small rills in its course, and working out a bed between the mountains, passes through a gap in the Blue ridge, and empties into the Susquehannah, fifteen miles above Harrisburg.

Back of us the woods with which one of the mountains was clothed was on fire. During the darkness of the night, the awfulness and sublimity of this spectacle were beyond description; terror mingled with it, for, as we were at no great distance, we feared that the shifting of the wind would drive the flames upon us.

Page 20 Monday, April 11 [1803]

We resume our journey; cross the two branches of the Juniata, and arrive at Bedford, the chief town of Bedford County in Pennsylvania, to breakfast. It is regularly laid out, and there are several houses on the main street built with bricks; even the others, which are of hewn logs, have a distinguishing neatness in their appearance. The Court House, Market House, and Record Office, are brick; the Gaol is built of stone. The inhabitants are supplied with water brought in pipes to a large reservoir in the middle of the town. On the northerly skirt of the town flows Rayston creek, a considerable branch of the Juniata.

Bedford was made an incorporate town in 1795. The officers of police are two Burgesses, a Constable, a Town Clerk, and three Assistants. Their power is limited to preserve the peace and order of the place.

Upon quitting the plain, we left a fertile soil clothed with verdure, and a warm and pleasing climate; but, as we ascended the mountain, the soil appeared more barren, and the weather became colder. Yet here and there we met with a little verdant spot

Page 21

around a spring, or at the bottom of a small indenture in the sides of the mountain. Climbing hence, the prospect widened. Deep vallies, embowered with woods, abrupt precipices, and cloud-capt hills, on all sides met the view.

In these mountainous scenes nature exhibits her boldest features. Every object is extended upon a vast scale; and the whole assemblage impresses the spectator with awe as well as admiration.

After many a wearisome ascent, we arrived at Seybour’s, on the top of the Alleghany; and, having ridden thirty-one miles, were sufficiently tired to accept even of the miserable accommodations this Inn afforded for the night.

Tuesday, April 12 [1803]

On leaving our lodging on “the highest of hills,” we had to descend through six miles of rugged paths, over precipices, and among rocks, and then along a miry valley, with formidable ascents in view.

The Alleghany, which we had now crossed, is about fifteen miles over.

We descried at a distance the towering ridges of mountains, beyond many an intermediate height; some encircled with

Page 22

wreaths of clouds, and others pointed with fire kindled by the hunters, or involved in curling volumes of smoke.

We were the principal part of the day passing the valley, and mounting Laurel Hill, which is about three miles in direct ascent, and lodged at Behmer’s near the top, after a journey of twenty-four miles.

As the woods were on fire all around us, and the smoke filled the air, we seemed to have ridden all day in a chimney, and to sleep all night in an oven.

Wednesday, April 13 [1803]

This mountain has its name from the various species of Laurel with which it is clothed; (Rhododendron Maximum, Kalmia Latifolia, &c.) There were several varieties now in flower, which made a most elegant appearance.

Our road, which at best must be rugged and dreary, was now much obstructed by the trees which had fallen across it; and our journey rendered hazardous by those on each side which trembled to their fall. We remarked, with regret and indignation, the wanton destruction of these noble forests. For more than fifty miles, to the west and north, the mountains were burning.

Page 23

This is done by the hunters, who set fire to the dry leaves and decayed fallen timber in the vallies, in order to thin the undergrowth, that they may traverse the woods with more ease in pursuit of game. But they defeat their own object; for the fires drive the moose, deer, and wild animals into the more northerly and westerly parts, and destroy the turkies, partridges, and quails, at this season on their nests, or just leading out their broods. An incalculable injury, too, is done to the woods, by preventing entirely the growth of the trees, many of which being on the acclivities and rocky sides of the mountains, leave only the most dreary and irrecoverable barrenness in their place.

We took breakfast at Jones’ mill, six miles from the top of Laurel Hill; dined at Mount Pleasant, eleven miles farther; and riding five miles in the afternoon, reached M’Kean’s to lodge.

We left Fort Ligonier, built by Gen. Forbes in 1758, to our right, and crossed the Chesnut Ridge, a very rough and rocky mountain, the last of the great range, on the Glade road. In dry seasons this is considered as much better that what is call-

Page 24

ed “Braddock’s road;” but, after heavy rains, it is almost impassable.

By the rout we took over the mountains the whole distance from Strasburg is one hundred and eighteen miles.

The road is very rugged and difficult over the mountains; and we were often led to comment upon the arduous enterprize of the unfortunate General Braddock, by whom it was cut. Obliged to make a pass for his army and waggons, “through unfrequented woods and dangerous defiles over mountains deemed impassable,” (See Gen. Braddock’s letter to Sir T. Robinson, June 5th, 1755) the toil and fatigue of his pioneers and soldiers must have been indescribably great. But it was here that his precursor, the youthful Washington, gathered some of his earliest laurels.

During the whole of this journey there are but a few scattered habitations, of a very ordinary appearance. The lands, except in the vallies, are of an indifferent quality, and offer but little encouragement to the cultivator.

The Alleghany mountains, which we had now passed, consist of several nearly parallel ridges, rising in remote parts of

Page 25

New-York and New-Jersey, and running a southwesterly course till they are lost in the flat lands of West-Florida. They have not a continued top, but are rather a row or chain of distinct hills. There are frequent and large vallies disjoining the several eminences; some of them so deep as to admit a passage for the rivers which empty themselves into the Atlantic Ocean on the East, and into the Gulph of Mexico on the South. It is only in particular places that these ridges can be crossed. Generally the road leads through gaps, and winds around the sides of the mountains; and, even at these places, is steep and difficult.

The rocks and cliffs of the mountains are principally grit, or free-stone; but in several places, particularly towards the foot, the slate and lime-stone predominate. Through the Glades, the slaty schist and lime-stone is abundant. On Laurel Hill, and the mountains westward of that, the fossil coal (Lithanthrax) abounds, and lies so near the surface that it is discoverable in the gullies of the road, and among the roots of trees that have been overthrown by the wind.

Page 26 Thursday, April 14 [1803]

Now that we have crossed all the mountains, the gradual and easy slope of the ground indicates to us that we are approaching those vast savannas through which flow “the Western waters.” The plain expands on all sides. The country assumes a different aspect; and even its decorations are changed. The woods are thick, lofty, and extremely beautiful, and prove a rich foil. A refreshing verdure clothes the open meadows. The banks of the brooks and river are enamelled with flowers of various forms and hues. The air, which before was cold and raw, is now mild and warm. Every breeze wafts a thousand perfumes, and swells with the gay warblings of feathered choristers.

“Variæ, circumque supraque,

Affuetæ ripis volucres et fluminis alveo,

Æthera mulcebant cantu, lucroque volabant.”

The painted birds that haunt the golden tide,

And flutter round the banks on every side,

Along the groves in pleasing triumph play,

And with soft music hail the vernal day.

The long and tedious journey we had passed, through lonesome woods and over rugged ways, contributed not a little, per-

Page 27

haps, to enhance the agreeableness of the prospect now before us. Certainly there is something very animating to the feelings, when a traveller, after traversing a region without culture, emerges from the depths of solitude, and comes out upon an open, pleasant, and cultivated country. For myself I must observe, that the novelty and beauty of the romantic prospects, together with the genial influence of the vernal season, were peculiarly reviving to my bodily frame for a long time weakened by sickness, and exhilarating to my mind worn down by anxiety and care.

We were now upon the banks of the Yohiogany River, which we crossed at Budd’s ferry.

The name of this river is spelt, by some writers, Yohogany, and by others, Yoxhiogeni; by General Braddock it was written Yaughyaughané; (Letter to Sir T. Robinson, June 5, 1755) but the common pronunciation is Yokagany, and the inhabitants in these parts call it “the Yok river.” It rises from the springs in the Alleghany mountain, which soon unite their streams in the valley, or, as it is called, “the great meadows,” below. The point where the

Page 28

north branch from the northward, the little crossing from the southeast, and the great south branch, form a junction, three miles above Laurel Hill, is called “the Turkey foot.” With the accession of some smaller runs, it becomes a very considerable and beautiful river. Pursuing a northwesterly course, as it passes through a gap in Laurel Hill, it precipitates itself over a ledge of rocks which lie nearly at right angles to the course of the stream, and forms a noble cascade, called “the Ohiopyle Falls.” Dr. Rittenhouse, who has published a description of these falls, accompanied with an engraving, found the perpendicular height of the cataract to be “about twenty feet, and the breadth of the river two hundred and forty feet. For a considerable distance below the falls, the river is very rapid, and boils and foams vehemently, occasioning a continual mist to arise from it. The river at this place runs to the southwest, but presently winds round to the northwest, and continuing this general course for thirty or forty miles, it loses its name by uniting with the Monongahela, which comes from the southward, and contains perhaps twice as much water.”

Page 29

The navigation of this river is obstructed by the falls and rapids below for ten miles; but thence to the Monongahela, boats that draw but three feet of water may pass freely, except in dry seasons.

The land in the vicinity of the river is uneven; but in the vallies the soil is extremely rich. The whole region abounds with coal, which lies almost on the surface.

We garnished our bouquet to day with the beautiful white flowers of the Blood root, (Sanguinaria Canadensis) called by the Indians “Puccoon:” they somewhat resemble those of the Narcissus. This plant grows in mellow high land. The root yields a bright red tincture, with which the Indians used to paint themselves, and to colour some of their manufactures, particularly their cane baskets. –The root possesses emetic qualities. –Transplanted into our gardens, this would be admired as an ornamental flower, while the roots would furnish artists with a brilliant paint or dye, and perhaps be adopted into the Materia Medica as a valuable drug.

At Elizabethtown, about eighteen miles from Pittsburg, we crossed the Monongahela. Having collected particular informa-

Page 30

tion respecting this river and the Alleghany, and an account of the settlements upon their banks, I insert it in this place. (Partly from a little pamphlet, published in Pittsburg, called “The Ohio Navigator,” with such other remarks as my own observation and inquiries could supply.)

The Monongahela takes its rise at the foot of Laurel Hill in Virginia, about Lat. 38° 30’ N. Thence meandering in a north by east direction it passes into Pennsylvania, and at last, uniting its waters with those of the Alleghany at Pittsburg, forms the noble Ohio.

The settlements on both sides of this river are fine and extensive, and the land is good and well cultivated. Numerous trading and family boats pass continually. In the spring and fall the river seems covered with them. The former, laden with flour, whiskey, peach-brandy, cider, bacon, iron, potters’ ware, cabinet work, &c. all the produce or manufacture of the country, are destined for Kentucky and New Orleans, or the towns on the Spanish side of the Mississippi. The latter convey the families of emigrants, with their furniture, farming utensils, &c. to the new settlements they have in view. These boats are generally called “Arks;” and are said to have been invented by Mr.

Page 31

Krudger [Kryder or Cryder], on the Juniata, about ten years ago. They are square, and flat-bottomed; about forty feet by fifteen, with sides six feet deep; covered with a roof of thin boards, and accommodated with a fire-place. They will hold from 200 to 500 barrels of flour. They require but four hands to navigate them; carry no sail, and are wafted down by the current.

The banks of the river opposite to Pittsburg, and on each side for some distance, or rather the high hills whose feet it laves, appear to be one entire body of coal. This is of great advantage to that flourishing town; for it supplies all their fires, and enables them to reserve their timber and wood for ship building and the use of mechanicks.

Find the remainder of Harris’s Journal at Google Books.